“We live from contemplation without even paying attention. There is this desire that is at the bottom of all of us that leads us to the contemplative life.” - Fr. Thomas Pikandieu Gomis, OSB

The journey to understand the contribution of Black Lives & Contemplation (BLC) to the contemplative movement, and to learn more about how to center Blackness in contemplation, began with a return to the roots of monastic life in Africa. During this time of discernment dedicated to exploring BLC's scope, I proposed a pilgrimage to the Abbaye du Cœur-Immaculé de la Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie à Keur Moussa, or, more simply, Keur Moussa Monastery, in Senegal to begin this process of discovery.

A journey to Africa holds profound significance, particularly for those of us in the African Diaspora. It is a necessary reconnection to ancestral lands, a space for healing despite the scars of colonialism and exploitation. As I began this journey, Shabaka Hutchings' spoken word track 'Song of the Motherland' remained in my mind, especially these lines which were written and recited by his father, Anum Iyapo:

'I am not magic / not a miracle / but I bring determination / I focus your consciousness on towards good / I motivate your unrelenting struggle / I energize the feeling spirit / believe in me / I am Blackness / I am identity / take me'

Written as if Africa's own voice were speaking to her children of the Diaspora, these words guided my voyage. This was a pilgrimage of contemplation, a reaffirmation of ancestral ties, and a period of deep reflection and prayer, all intended to guide this time of discernment.

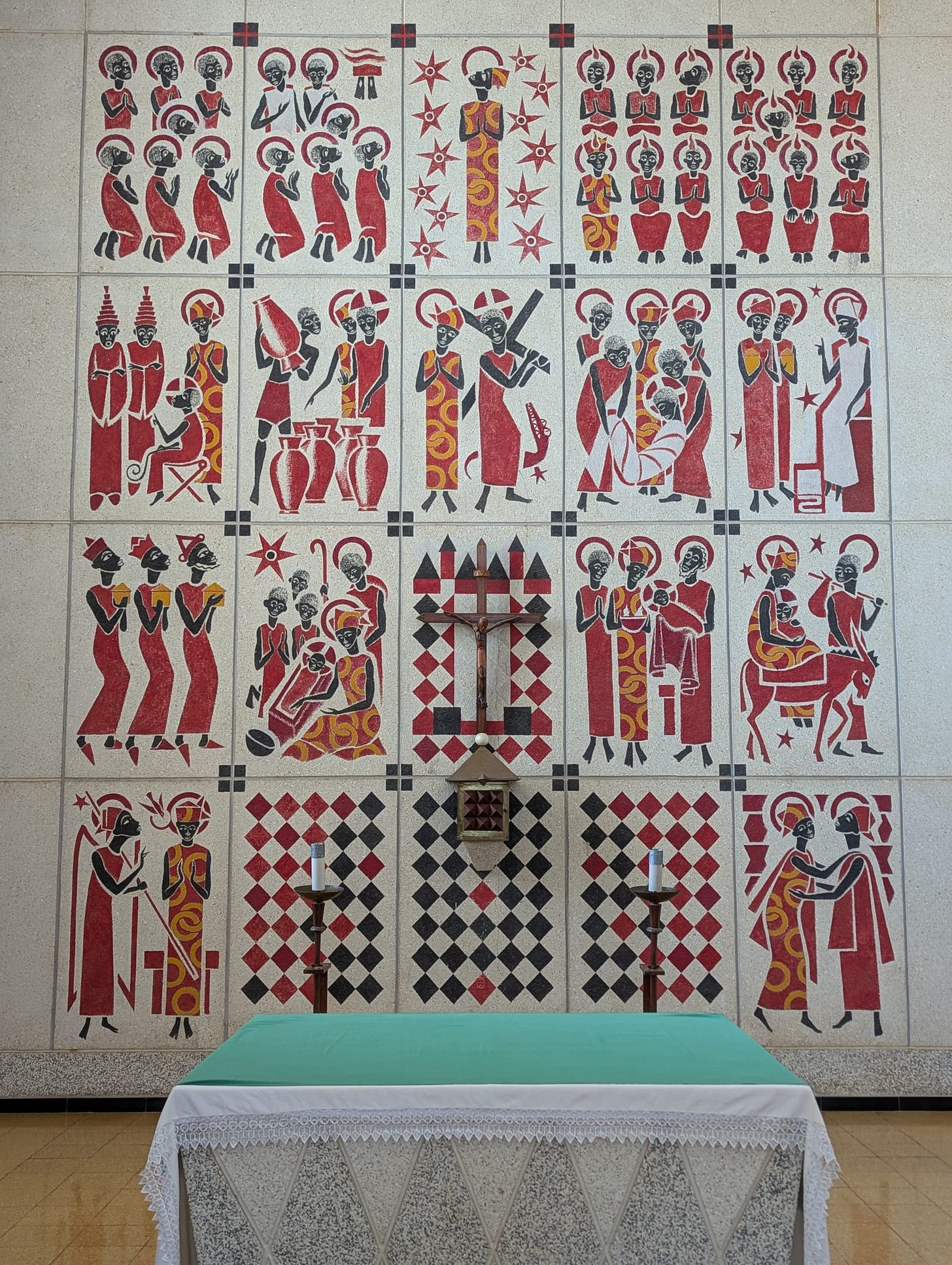

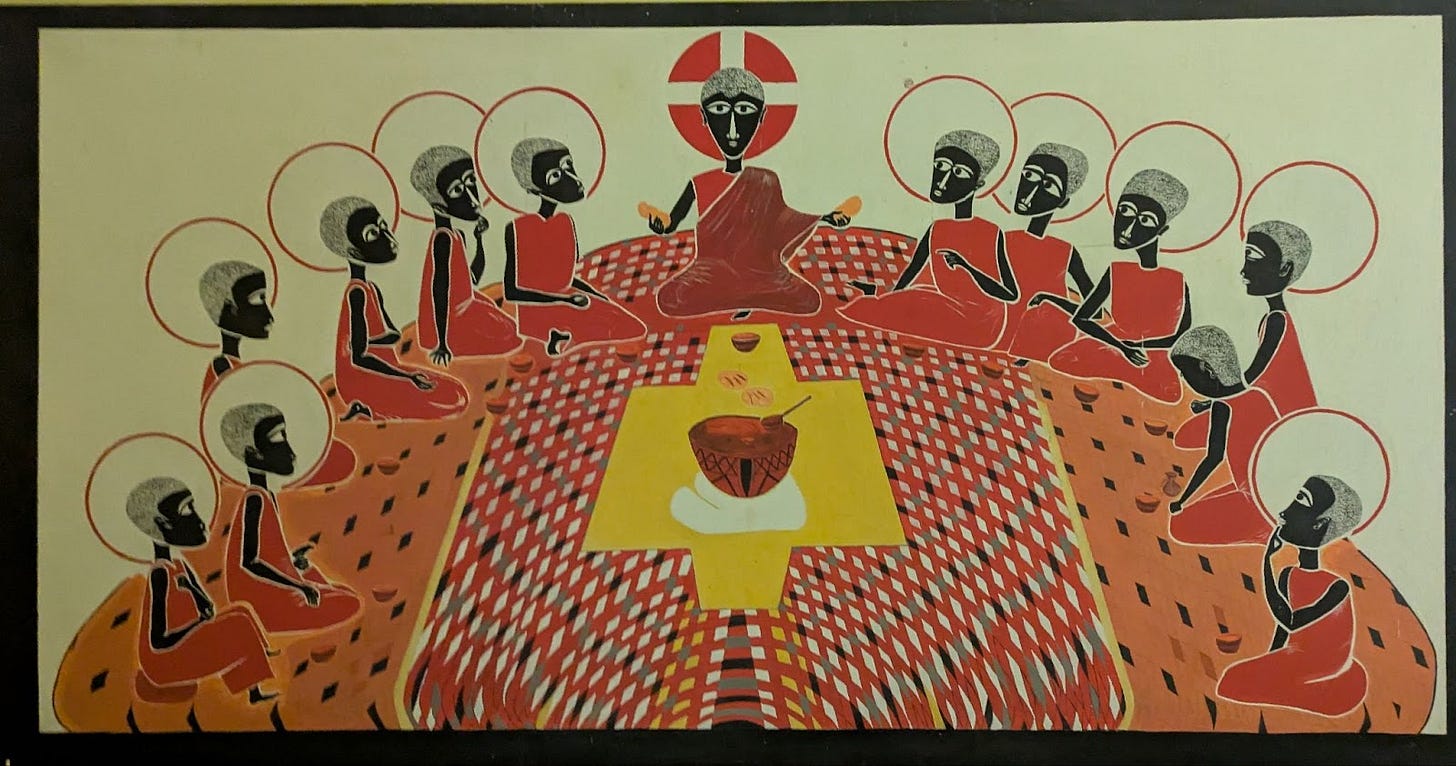

I had known about Keur Moussa for some time, especially due to the frescoes in the monastery's church. These paintings are world-renowned for their unique portrayal of biblical figures like Mary and Jesus as Black, or more accurately, as Senegalese. Keur Moussa itself is a monastery established in 1961 by Benedictine monks from the Solesmes congregation in France. (The Solesmes congregation has a fascinating origin story, which you can delve into further here). Going to Keur Moussa was a pilgrimage for me. From the moment I learned about it, I was determined to go there and pray with the brothers. I longed to see the frescoes in person and experience what it was like to center Blackness during my time of worship.

My pilgrimage to Keur Moussa, and then onward to Keur Guilaye—more to come on this aspect of my journey—was a very enriching experience, as all pilgrimages tend to be. I started my journey on February 13th, beginning with a meaningful stop: sharing thoughts on the importance of contemplation for Black life at a Children's Defense Fund retreat at the Alex Haley Farm. The presence of such deep-rooted Black history and providing a power, at the farm of Alex Haley himself, felt like a powerful and perfect prelude. This centering of Blackness, just before my departure for a monastery that also centered Blackness, felt remarkably appropriate, like a divinely orchestrated beginning to my spiritual journey.

The depth of the ancestral presence and the profound sense of liberation at the Alex Haley Farm will be something I write more about later. But, for now, it's essential to note that this stop was pivotal. It served as a powerful and fitting transition, launching me from the hustle and bustle of Brooklyn to the tranquility of the farm and then onward towards Keur Moussa, it provided a deeply resonant introduction to my journey to the motherland. Imani Perry's "Black in Blues" and Zeinab Badawi's "An African History of Africa" were invaluable companions on my journey, deepening my understanding of Blackness.

After a brief sojourn in southern Senegal and then Dakar, I arrived at Keur Moussa. The monastery's location was a revelation, a peaceful enclave within a remote, predominantly Muslim town, reflective of Senegal's strong Muslim presence. The monastery's respected presence amidst this community was remarkable. The daily experience of the muezzin's call intertwining with the Vigils was a profound moment, a beautiful and unexpected symphony of faith. Arriving after a solitary journey through Senegal, compounded by my lack of French, you really need to know French in Senegal. I was met with the warm embrace of two brothers, whose humor and kindness instantly made me feel at ease and provided an immediate sense of belonging.

Keur Moussa, like all monasteries, has its own unique character, but it stood apart from any monastery I had previously experienced. As soon as I arrived, I was asked to wait for Brother Thomas, the guestmaster, who greeted me with evident joy, finally meeting after months of emails. Before my retreat began, he gave me an unusual instruction: to present myself in the church. This was a new experience for me, having visited monasteries for over a decade, never have I been asked to consecrate myself in the church. Entering the church, I was met with the striking sight of the frescoes portraying the Black Holy Family. I immediately realized I wasn't just presenting myself to the church; I was offering myself in prayer before images of Christ, Mary, Joseph, the disciples, and angels, all reflecting African features. It was a representation of the divine that more closely resembled my own image, a profound spiritual moment that left me in silent awe and all I could do was bow.

I should briefly say something about Brother Thomas, as his story is a testimony of profound transformation. A striking figure, tall and statuesque, he arrived at Keur Moussa over two decades ago, not as a seeker, but as a committed Marxist revolutionary. His initial antipathy towards Christianity was rooted in its colonial legacy in Africa. Yet, through his involvement in social protests, deep scriptural study, and sustained dialogue with other monks, a different vision of Christianity emerged – one centered on liberation. This resonated deeply, leading him to embrace monastic life, a path he saw as both personally grounding and a means to contribute to the liberation of others. Brother Thomas spoke very little English, and I speak no French, but he generously shared his thoughts on contemplative life with me as much as possible, a true testament to his openness and depth.

During my time at the monastery, I made a conscious effort to engage with the frescoes during each liturgical office. I participated in nearly all twenty-four offices available during my retreat, missing only one due to a brief pilgrimage within my larger journey. The frescoes, strategically positioned on the church's main wall, served as a central point for contemplation during every single office. When I had a chance to chat with Brother Thomas and asked him about the frescoes, he explained that “We, Black people, need to familiarize ourselves with praying before Black images. We need a visual gateway. To fully embrace faith, especially Christian faith, we require visual access, and Christian art provides that. These frescoes, rendered in flat, expressive tones of black, red, yellow, and white, while maybe not very elaborate, are expressive. They mean something.”

And so, I did just that. The more I prayed alongside them, engaging with them in a meaningful way, the more familiar they grew. Their initial sense of novelty and awe faded, replaced by a feeling of naturalness and a sense of a profound connection. They are, without a doubt, holy images.

Music also served as a powerful expression of Black (more specifically Senegalese) cultural centrality at Keur Moussa. Initially, the French founders considered importing an organ to the monastery for their monastic offices but some of the brothers opposed that idea and advocated for incorporating Senegalese rhythms to attract more Senegalese who may be called to the religious life. This led to the adoption of traditional instruments like the balafon, djembe, sabar drum, and, most notably, the kora- a 21-stringed West African harp lute. Keur Moussa is renowned for its uniquely designed kora, adapted specifically for liturgical use. The resulting monastic offices are unlike any other I have ever experienced, blending traditional Senegalese sounds with Christian liturgy. The rhythmic pulse of the drums, the melodic resonance of the balafon, and the intricate harmonies of the kora create a worship experience where every prayer, in sound and imagery, is deeply rooted in African cultural expression. This article provides even more detail about the music at Keur Moussa. The monastery was thriving, filled with many young, active brothers engaged in all of the activities of the monastery, which includes a farm, a retreat center and of course the making of the Kora. Its diversity was also striking, with monks from Senegal, Guinea, Gabon, Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Burkina Faso, Gambia, and France.

Monastic life is rich in daily rhythms. Those who have experienced a monastery retreat know how deeply one can become attuned to these rhythms and find joy within them. However, during my stay, I learned of the Abbaye de Saint Jean Baptiste - Keur Guilaye, a neighboring monastery featuring equally striking frescoes of John the Baptist, and other Christian figures. I decided to integrate a mini-pilgrimage into my current pilgrimage to visit these other representations of St. John the Baptist, one of my favorite biblical figures, since it was not that far from Keur Moussa.

I decided to make the journey to Keur Guilaye on foot so that it felt more like a pilgrimage. I brought a rosary, both as a tool for prayer and as a symbol of respect, observing the many Senegalese men carrying Muslim prayer beads. The walk, though long, was direct and easy to follow. Upon reaching the monastery after approximately sixty minutes, I was immediately struck by the beautiful frescoes depicting John the Baptist's life and a powerful Christus Victor, as Senegalese. I prayed when I saw the frescoes, but couldn’t spend much time examining them up close. The sisters were engaged in a moment of deep adoration, and I respect that spiritual practice too much to interrupt it by acting like a tourist. Before departing I met a wonderful nun, Sister Miriam (the name Miriam holds a very important significance for me and it was not lost upon me that I was greeted by Miriam) who approached me and said, “I hope you are not disappointed by the church.” I didn't understand what she meant, but I assured her that I was deeply moved by the images. I shared how important these Black representations of John the Baptist and Jesus were to me. She responded, “Yes, we want to make God's kingdom known to all, and these images help people see God within themselves.”

These words by Sr. Miriam made me reflect on this pilgrimage in Senegal. All of these moments reinforced the impressions I gathered throughout my stay at Keur Moussa, and during my brief visit to Keur Guilaye. I witnessed two communities, each dedicated to their contemplative callings, thriving in a largely Muslim environment. This led me to recall a conversation with Brother Thomas. When I asked him about his views on contemplation for Black people he responded, “Because of the many societal ills, our nature has been wounded. Truly, all of human nature has been wounded by the stain of racism and the plundering of Africa by Europe. Therefore, the contemplative life serves as a remedy, an antidote to these afflictions.” For the brothers at Keur Moussa and the sisters at Keur Guilaye, the contemplative life has been what gives them life and centering their Blackness in this contemplative life provides a way for them to truly worship in spirit and in truth. I hope to continue to learn from their examples. The Spirit led me to this place where I could learn from these communities, because, as Brother Thomas also told me, "We are all interdependent, we need each other, and we cannot evolve on our own.”

The full scope of what I learned during this retreat is still unfolding within me. Each day since returning from Keur Moussa I recall something that changes my mood and gives me a new perspective. I believe that as with all pilgrimages, the insights will reveal themselves to me over time. But what is immediately apparent is that centering Blackness in the images, the community, the music, the food, and every aspect that I experienced while in Senegal provided a profound sense of welcome and spiritual renewal. As Brother Thomas told me during another one of our brief conversations, “We live from contemplation without even paying attention. We come from contemplation.” If we pay attention to the subtle nudges that guide us toward contemplation during our quotidian lives - a moment in the park, listening attentively to a piece of music, a silent moment before we step out into the world, a heartfelt embrace with a loved one - we will discover that our daily lives, when listened to, can lead us to a deep contemplative life. This, I believe, allows us to ground our identity in the Divine, thus enabling us to help others see the Divine within themselves.

Guesnerth Josué Perea serves as Director of Black Lives & Contemplation and is a novice of the Community of Incarnation. He also serves in other capacities as Associate Pastor at Metro Hope Church, Executive Director of the afrolatin@ forum, Co-Curator of the AfroLatine Theology Project, Executive Producer of the documentary "Faith in Blackness: An Exploration of AfroLatine Spirituality”, and Co-Host of the podcast Majestad Prieta. His perspectives on AfroLatinidad & Blackness have been part of various publications including the New York Times, the New Yorker, and Sojourners & his writings are a part of Let Spirit Speak! Cultural Journeys through the African Diaspora, the Revista de Estudios Colombianos, and Engaging Religion among others.