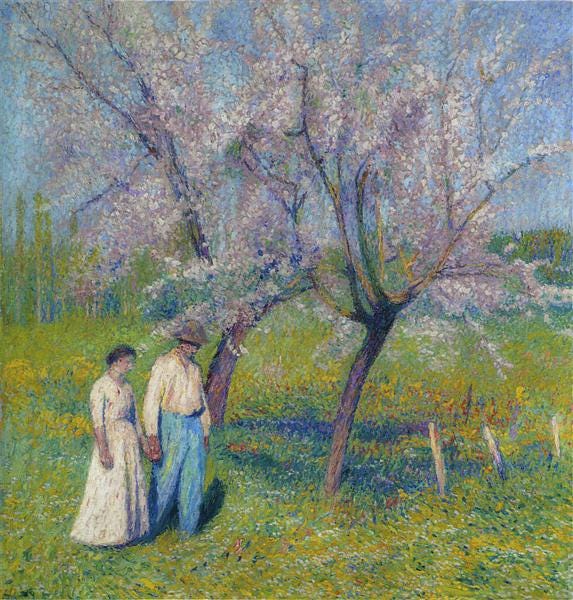

Promenade de Fiancees sous les Pommiers by Henri Martin, XIX-XX Century

A memory, small and vivid, from my wedding day slips in my thought stream. My wife and I were married lakeside in Michigan on a muggy June morning a decade ago. Minutes before the wedding procession was set to begin, my nephews and I were occupied ourselves by kicking around a soccer ball. Back and forth we went with bouts of bruised shin laughter. I remember thinking, is this what one does minutes before they take marriage vows? Kick around a soccer ball? Turns out that, yes, this is what one does before they take marriage vows.

Ten years after my wedding vows, here I am readying myself to make solemn vows as a member of the Community of the Incarnation. As the procession into the vow ceremony was about to begin I was outside the Cathedral chopping it up with fellow community members. Is this what one does before taking monastic vows? Joke around with friends? I thought of my nephews and I kicking the ball around, dusting up our wedding duds. Yes, this is what one does before taking monastic vows.

Life is a series of wagers that follow the bumper moments of the everyday, like kicking around a soccer ball or mixing it up with friends. It took me until my early thirties to realize, to really realize, that this life is serious business in its mundanity and you don’t get doused in joy, abundant life, or meaning without risking commitment in the daily hullabaloo.

My twenties were an unfocused and adventurous romp with Merle Haggard’s “Ramblin’ Fever” as my anthem; seeking footloose Keruoacian travel while desiring to be in Divine connection and service like Brother Lawrence of the Resurrection. These two stars were a formative constellation charting my course. Self-assigned navigation settings to shape my soul. In pursuit of the ever elusive “it”, my risk tolerance for venturous experiences expanded, while I took my knocks and bumped into dead ends, I noticed that my interior self was moving at a slower clip. This gave me pause. The fear and trembling required to wade through the internal sludge required risk, and maybe commitment, that I was denying. It was then I noticed the constellation guiding me was set against a much larger night sky and the idea of giving myself over to the vulnerable, unpredictable, enormous, unknown relationality with God and others that darkness represented was stultifying.

I was blocked by dueling desires; a certainty of relational outcomes and to be free of all constraints. These desires cut me off from commitment on both ends of the stick. I learned to use that stick to prop open an escape hatch. When I couldn’t guarantee an ending or my freedom felt curbed, when it was time for me to bail I popped out the escape hatch. The desires that propelled me, blocked me. Until a guileless desire for union with an unkempt God began to mushroom. I longed for this homecoming with an unaddressed hope that perhaps I could retain my compulsive desires too. In this stuck place, questions haunted me. How do I get a safety net stretched below in case the way of love drops me? If these commitments don’t work out, can I catch that ramblin’ fever again? What if I get brutalized by the bloody fists of reality? Maybe if I peek behind the curtains of Mystery I can inquire about taking out an insurance policy on my ontological integrity and love? Geez. Secretly I was hoping for signs on billboards or serendipitous situations to resolve these problems. But no signs appeared other than the sign of Jonah. Finally I realized these were not problems to be solved, but mysteries to bear. This slow dawning of the commitment required to stay open became real. Control is a figment. Life is plain messy. Discernment is a dance. Escape hatches only return you to sender. The poet Carolyn Forché says, “The silence of God is God”. I get it. I give up.

Compartmentalizing life is too tidy. It keeps one slightly neurotic in their preferred framework of self approved integration plans. For me, it was a fictionalized version of Jack Kerouac and a very real Brother Lawrence. Exterior adventure and internal examination. Risk and safety nets. Self-direction and commitment. Insurance and mystery. These antinomies kept me going, and somewhat healthy, in necessitating a life of creative tension that did not devolve into commercial answers but resolved in ragged discernment. A discernment that exposed the gaps in my curated project called the self. For without a great wager, a daring surrender of the self, or a falling overboard into the fathomless Love of God, what was I doing with this “one wild and precious life”1? I was escaping immersion by settling for a breezy mist on the bow. Vows, be they marriage or solemn, are these invisible passages that concretize incarnational responses to an ineffable Divine invitation expressed through mundane, heartworn words within a community and God. That is full body immersion. Avowed commitment is stepping into an untamed river to be swept off your feet, radicalized by consenting to a mysterious force whose name is nicked God.

Forgive the corner store preaching preamble on vows. It felt necessary to empty my pockets of the ruminating lint that led to my lived understanding of vows. It has been decades in the making and brought me to taking vows with the Community of the Incarnation.

Let me salvage this meandering, reckless musing by quoting folks wiser than I, as responses to catechism-like questions that followed me home like a friendly stray to our vow ceremony .

What Is Your Purpose?

In Josef Pieper’s dainty book Only the Lover Sings he quotes 5th Century BCE Greek philosopher Anaxagoras who when asked, “Why are you here on earth?”, Anaxagoras replied, “To behold.”2 A Greek expression that would be translated into contemplatio by the Romans. We are meant to be beholders. The rhythm and rule of life of the Community of the Incarnation is the trellis that befits this purpose for growing into a beholder.

Am I Called to Vowed Life?

Discerning a vocational struggle begins in existential examination. Carmelite Wilfrid Stinissen offers a “typical example of an inner attraction that comes from God [in] the vocation to religious life…one often asks: “How can I know that I am called?” It is generally not by a voice from heaven that tells us what we must do, but rather by a growing inner certitude of a divine invitation; a certitude that is then confirmed by the peace one experiences when, after much rebellion and a long drawn-out struggle, which shows one understands the seriousness of the call, one finally surrenders to God.”3 Certitude is not a word I would use, but rather, a confirmation that the divine invitation has been read and received. The desire to follow through is met by equal portions of resistance, fear, and ineptitude. Wrestling with these wildcats sharpens a defensive stick to keep them at bay. This is when surrender occurs. Energy expelled in the struggle exemplifies the seriousness of which one takes the call, then one of the aforementioned wildcats licks you. Then the other two nuzzle you. Somehow, in some unintelligible way, the wildcats have gotten domesticated ever so slightly (or you have been rewilded), changing the relationship forever. You drop the defenses. The call turns into a deeper fall into Mystery.

How Do I Trust the Call?

The Midwest marauder of lukewarm souls, Bill Holm, writes, “The divine lives in all the human, and the human lives in all the world, or nature if you wish, or the planet speeding along under foot if you like that better. Sacredness is unveiled through your own experience, and lives in you to the degree that you accept that experience as your teacher, mother, state, church, even, or perhaps particularly, if it comes into conflict with the abstract received wisdom that power always tries to convince you to live by. One of power’s unconscious functions is to rob you of your own experience by saying: we know better, whatever you may have seen or heard, whatever cockeyed story you come up with; we are principle, and if experience contradicts us, why then you must be guilty of something.”4

Can you trust the experience that brought you to this vocational call? The sacredness unveiled in your life? I dare you to. Get a smidge clear on the sacrality of your life and the belovedness of this Christ-soaked world and get ready to tip over. When you start to think dangerously about your life, you need to find people who can reflect back truth and wisdom in this light. Community like this provides a secure container to ask hazardous questions and mirror qualitative responses. This smacks the face of the Empire with a potato sack. Empire prefers to suck up meaning with a straw and sell it back to you in sugary overpriced forms. Empire is baffled when you wrestle with the counterculture communal invite, revealing the incarnational unveilings in your experience, and squeezing out the systems of domination between your cheeks. This is new monasticism. Beverly Lanzetta writes “new expressions of monasticism are not only authentic, but also offer a vital and necessary counterpoint to secular society.”5 This ain’t easy, but this is where there is life. In a community that listens to the internal questions nudging you forward, encouraging you to bear and trust the Mystery with wonder and gratitude. Dropping eternally without a safety net with a community, you become more free to hear and respond to the cry of the poor and the cry of the earth. One might even call this type of community, “church”.

Why Take Vows?

There is a poem (or maybe its poetic advice) by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe called “On Commitment”6 with an outsized impact on my life. Commitment used to scare the hell out of me, first metaphorically and then in actuality. Someone printed this poem out and handed it to me. That small act of intuition changed my life forever. Goethe writes,

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy,

the chance to draw back.

Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation),

there is one elementary truth,

the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans.

That the moment one definitely commits oneself,

then Providence moves too.

All sorts of things occur to help one

that would never otherwise have occurred.

A whole stream of events issues from the decision,

raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents

and meetings and material assistance,

which no man could have dreamed would have come his way.

Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it.

Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.

Begin it now.

We take vows to commit, to join in a sacred direction and release other paths. They crack a window for the inrushing of God. There is an intuitive yet inarticulate enchantment compelling me towards these vows. This is not magical thinking or clinging to a fortress named vow. Vows are how a marriage opens up room to breathe. Or how a vocation is foretasted. Or how a community becomes worthy of its intent and call. The gift of the vow is ripened in the thisness of this person who hears this vocation call within this community. These wagers, these bets, release the unspoken unknown possibilities for the sake of what is specifically alluring one into a larger mystery. Vows are verses in an epic poem7. The vows I have taken in my life are few. They have been met with years of discernment and care, and finally a shaky surrender. One thing nobody ever told me about taking vows was that after the deep sifting period of preparation, a focused freedom is offered as an ongoing conversion of life. A freedom from distraction and freedom for direction.

What are the vows of the Community of the Incarnation?

The vows of the Community of the Incarnation are:

I commit to a new monastic rhythm of life:

I commit to an “ongoing conversion of life:”

I commit to live my spirituality in the context of “hearing and responding to the cry of the poor and the cry of the earth”:

I commit to living this Rule of Life with the Community of the Incarnation.

In an age of breakneck spirituality and transactional relationships, these simple vows took years to be readied into and our community is trusting the call to live them out together. We are at the beginning of this life together with our newly seeded vows. Joan Chittister says that “the really important thing to understand is that monasticism is not an efficient system; it is a patient one, however. It is about growth, not conformity. The dilemma is that growth is slow. Everywhere. In everything.”8 There is no arrival in the business of vows. There is no flashy ending. There is more of the same. Soccer balls and jokes. The unending pattern of life, death, and resurrection.9 Listening and responding to the cries of the poor and the planet. Steady love at the speed of relationship. I am drawn to the seriousness of what we at the Community of the Incarnation have begun and what we are formalizing together on the heels of the everyday.

Reflecting on the back bumper of these vows, I can see my first step towards them began years ago when I applied to be a Candidate with the Community of the Incarnation. Four years have passed and now we have taken our final vows. We bend towards them, to free us for a direction we are called to by God but cannot guarantee. There are no safety nets or assurances of success. Vows are quietly exercised in the commons. Neither rushing or resisting, I practice our vows at a walking pace within the conditions of my everyday life. What comes to my lips as a prayer is a riff off the mighty poet Machado, we make the vows by walking.

Lord, have mercy. Christ, have mercy.

Paul Swanson works at the Center for Action and Contemplation and is a contemplative shoveler at Contemplify. He is a vowed member of the Community of the Incarnation and a jackleg Mennonite who attends Our Lady of the Tall Trees. Paul lives in New Mexico with his wife Laura and their two feral, but beloved, children.

Interested in learning more about our New Monastic Community? Learn more at spiritualimagination.org/events

To quote the unmatched Mary Oliver’s poem “The Summer Day”

P.72 Josef Pieper, “Three Talks in a Sculptor’s Studio” in Only the Lover Sings: ARt and Contemplation (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1990), 72.

Wilfrid Stinissen, “Try to Discern the Will of the Lord,” in Into Your Hands, Father: Abandoning Ourselves to the God Who Loves Us (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2011), 54. ,

Bill Holm, “The Grand Tour,” in The Music of Failure. (Marshall, MN: Plains Press, 1985), 12.

Beverly Lanzetta, “The New Monk,” in The Monk Within: Embracing a Sacred Way of Life. (Sebastopol, CA: Blue Sapphire Book, 2018) , p.41.

I have also heard this is misattributed to Goethe, but have found no appropriate citation to him or anyone else.

This is a wonderful metaphor that mythologist Martin Shaw breathes life into on this podcast. He compares epic Christianity and lyrical Christianity.

Joan Chittister, “Stability: On Perseverance,” in The Monastic Heart: 50 Simple Practices for a Contemplative and Fulfilling Life (New York: Convergent, 2021), 158.

Read Katie Gordon’s top shelf piece, “Why not be utterly fire?” on the daily implications of this pattern in monastic life.